Universities have rightly invested in student mobility initiatives in recent years, from the European Union’s Erasmus scheme to a growing number of bilateral partnerships criss-crossing the world. The evidence is clear that travelling abroad can expand a student’s cultural frame of reference, build experience, and character, help with life skills like budgeting, and widen their network of peers, friends, collaborators, and employers.

“Mobility is not just subject matter content; it is the experience in the classroom and campus that adds to cultural experience” notes Carmel Murphy, Executive Director, International, of the University of Melbourne. In short, physical mobility gives a student an education they could not find in a textbook. Indeed U21's 2020 study showed that students who study abroad report higher rates of academic performance, and improved employability.

However, the pandemic forcibly curtailed study abroad programmes and universities, students and staff are understandably restless to re-start international travel. But the freeze has also been an opportunity to re-examine some of the shortcomings of conventional physical mobility initiatives and to prompt a frank discussion within the higher education community about ways their mobility partnerships might be falling short.

“The silver lining of the last 18 months is that we have had time to reflect upon what we are delivering,” says Yuhang Rong, Associate Vice President for Global Affairs at the University of Connecticut. “Many mobility programs have been of questionable validity, with islands of students sticking together and not interacting with local context”.

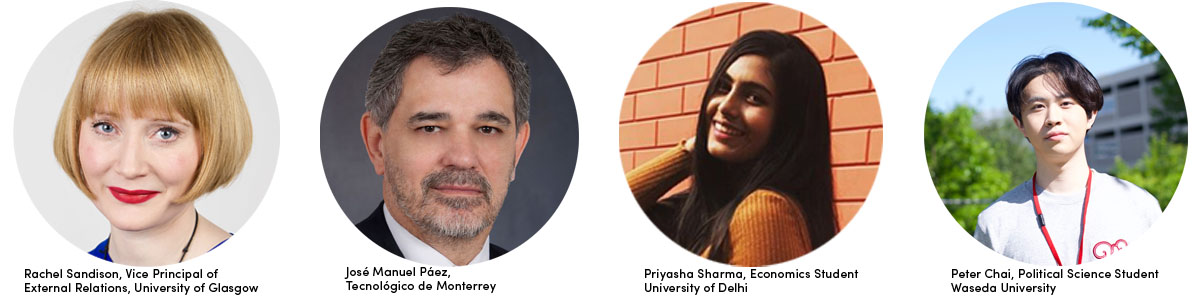

Rachel Sandison, Deputy Vice Chancellor - External Engagement and Vice Principal - External Relations at the University of Glasgow, agrees. “The pandemic has been a catalyst for higher education to think about what it is delivering in student mobility and how it could be improved”.

Two problems stand out. One is equity. The cost of going overseas to study are prohibitive, in both financial terms and time. Those from lower socio-economic backgrounds may need to work part-time jobs to fund themselves through university, for instance, or have care-giving responsibilities. “Are we advantaging the already advantaged? This question weighs heavily on our minds,” says Fiona Docherty, Vice President of External Engagement at UNSW Sydney.

Sustainability is the second. All universities are having to think carefully about their carbon footprint to make sure they are leading the way in fighting the climate crisis. Alan Mackay, Deputy Vice-Principal International and Director of Edinburgh Global at the University of Edinburgh, calls today a period of “climate-conscious internationalisation,” for the sector, whether that be academic travel and conferences or student programmes. He says the University of Edinburgh’s international travel was growing at 15% a year prior to the pandemic, equating to 20,000 tonnes of CO2.

Virtual and digital technology has been a godsend to the education sector - as it has for society as a whole - during the last two years. Digital platforms have proven their immense economic and social value both in areas where it was understood but under-utilised – like telemedicine, for instance – as well as in fundamentally new domains. Could digital tools help to expand the practice of student mobility in ways that address the deficits of the physical kind?

“Virtual mobility is often considered the ‘poor relation’ of a physical experience – but it can and does help answer these equity and sustainability challenges,” says Ms Docherty. “It offers scale, accessibility, negates the need for travel, and can be tailored in a way to build a range of skills in students beyond the curriculum”.

In this vein the U21 network is building a roster of projects that harness the unique power of online platforms to bring together students from different contexts, cultures and countries in ways that physical programmes may not be able to. The Global Citizens initiative, for instance, is a leadership and collaboration course bringing together 2,000 students from around the world to learn about the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and share ideas and perspectives on the global sustainability crisis. This is making a real difference in helping nurture students interests in this vital topic and the personal and cultural development that are “a must for education and should be in the mindset of every university” (Dr José Manuel Páez, Tecnológico de Monterrey).

“Our environment always fascinated me. While I know about the SDGs, I was not aware of the direction I should go to make a difference,” says Priyasha Sharma, an economics student at the University of Delhi. The U21 Global Citizens programme showed me that direction by teaching me several aspects of leadership, like interacting with people from diverse backgrounds and how to build the bridge which concatenates ideas and execution”.

A sense of community and peer support is another benefit, says Peter Chai, a political science student at Waseda University in Japan. “I was strongly inspired by the fact that so many students and researchers who are of the same age as me are also interested in learning about and trying to understand the challenges our societies are facing. Although we come from different countries and degree programmes, I felt that we share similar enthusiasm to make the world a better and more inclusive place. I came to understand that many social issues such as environmental protection and gender equality should be addressed with collective efforts across borders, and that certain things are universally shared by mankind, such as compassion”. Chai adds that virtual programmes have given people like him a chance to “learn more about the lives and ways of thinking of students in Europe and Oceania, that were previously limited”.

However, it is not just online courses being developed. Following the lead of universities such as The University of Auckland who offered 1500 virtual internships for students not able to travel and UNSW that pivoted their leading work-related learning programmes to online delivery during the pandemic, U21 is providing micro-internships offering employability experiences to students who may otherwise lack this opportunity.

As well as offering its own programmes for students across its 27 members during the pandemic U21 has also offered vital funding allowing members to develop their own innovative international programmes. Tecnológico de Monterrey as one such recipient has developed a global classroom initiative partnering with other U21 universities on short-course online mobility initiatives, also with a sustainability focus.

Rather than seeing virtual mobility as an inferior stop gap during the lockdown era, argues Ms Docherty, we should ‘dial up’ the differences between virtual and physical. Structural changes to higher education do, in many respects, favour virtual formats. Micro-credentials, the growing importance of collaboration and project work in today’s globalised world of work, and the phenomena of fast-changing skills sets, from coding to cybersecurity, all reflect a new world in which learners must continually expand their knowledge, rather than simply relying on graduating in a single academic subject at a single point in time. Digital competency is itself a skillset that students need to flourish in today’s technology-saturated world, and virtual learning and collaboration gives them useful first-hand experiences.

Online programmes can be designed to favour groups that had been disadvantaged in the physical mobility era. “There are great benefits for students to attend virtual global events. We are on a tight schedule and limited budget, so participating in person can be a struggle” says Elsa Sjödahl, Lund University, studying Engineering.

One example of such a programme is a collaboration between the University of Nottingham and the Universitas 21 network, which offered a global leadership course tailored to undergraduate students with limited or no previous international travel experience, or who came from low household income families.

Of course, virtual forms of mobility have many pitfalls – as does virtual learning. High drop-out rates, lack of motivation and potential inequality, with some students better able to learn from home than others – have all been struggles in education more broadly. But universities can take steps to address failings and shortfalls and think creatively.

The University of Melbourne are exploring how students can undertake internationalisation at home and in country by “engag[ing] in indigenous knowledge and exploring ways to bring this into the learning experience in terms of Australia’s heritage [and] building this with partners such as the University of Auckland and New Zealand’s Māori population, McMaster University and Tecnologico de Monterrey” [Carmel Murphy]. Meanwhile UNSW has established two ‘communities of practice’ to share knowledge amongst academic programme leaders and is actively learning from experience. For instance, one pilot, international virtual internship, showed that relationship-building between students and alumni works best when support staff continue to ‘hand-hold’, checking in on progress and stimulating action.

Therefore, through careful design and review, it is possible for universities to think more broadly about student mobility, leveraging the best of the physical and the digital to create ‘mobile minds’ that can flourish in today’s world. U21 sees these challenges as emblematic of a much wider re-think about the role that virtual engagement can play in a climate-conscious international higher education sector.

With thanks to our contributors:

- Date